Article by: Aisling Carroll

Disaster service workers from the County of Santa Clara check a client’s temperature. Photo credit: County of Santa Clara Health System.

For five years, David’s hammock was his home along San Jose’s Guadalupe River. He previously lived on a boat in the Berkeley Marina before his fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome made him too sick to work as a network architect and contractor. Unable to pay the docking fees and not wanting to burden his family, he moved into the hammock with two sleeping bags and a foam pad.

“Homelessness beats you up. It’s like you’re a boxer who had a long career,” said David, 43. He averaged eight ER visits a year, not counting urgent care.

When COVID-19 emerged in early 2020, unhoused people in Santa Clara County like David were assessed and relocated by the County. Those who had contracted or been exposed to COVID-19 or were at high risk for serious illness could shelter at one of 14 hotels leased by the County.

To staff the hotels and emergency shelters, the County of Santa Clara reassigned employees as disaster service workers (DSWs). Overnight, this diverse workforce of community workers, library warehouse assistants, park and probation employees, was deployed and plunged into entirely new roles.

Alicia Anderson, senior manager at the County’s Department of Behavioral Health Services, trained DSWs who “did not have a lot of experience working with folks experiencing homelessness.” A week-long crash course, which she helped design and deliver with others from the County’s Office of Supportive Housing, covered the knowledge and skills for DSWs to nonjudgmentally work with people possibly in crisis. Workers also learned how to try and keep people safe from COVID-19 at a time when there was a scarcity of personal protective equipment and a surplus of fear.

Checking in, with chronic illness

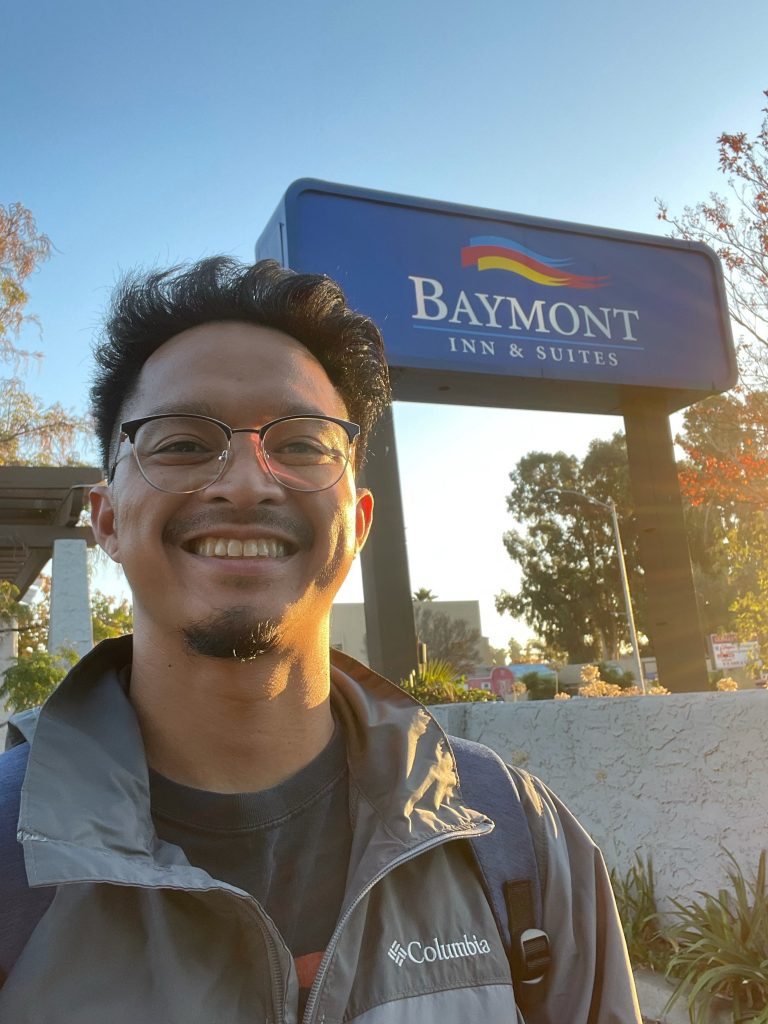

At one of the hotels, Adrian Malimban, who had previously served as a community health worker at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, worked alongside other DSWs, County employees, and longstanding partners, such as Abode Services and LifeMoves, to manage day-to-day operations.

Going door to door, he took temperatures, checked for symptoms, provided hygiene kits, meals, and medications. Crucially, he identified clients who might need COVID-19 testing or other medical attention and would tee up the clinical teams who were regularly on site.

“They were all complicated situations.”

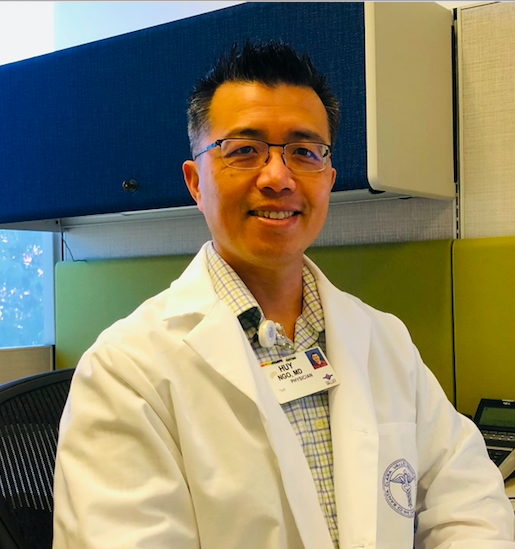

– Dr. Huy Ngo

Physicians and health care workers from Santa Clara Valley Medical Center’s Valley Homeless Healthcare Program (VHHP) would tend not just to COVID-19-related issues at the hotels and shelters but to people’s chronic illnesses and other medical conditions that had gone unaddressed: The heart disease and manic episodes in need of medication. The open leg and arm wounds in need of dressings. The unsteady and dangerous gaits in need of walkers.

Each client rarely had just one issue. Instead, there were multiple and co-occurring medical and social needs. “They were all complicated situations,” said Dr. Huy Ngo, who provided medical care at the hotels. He also works at the Hope Clinic, which provides primary and behavioral health care and social services, all under the umbrella of VHHP and part of the County of Santa Clara Health System.

Take the man who had been using methamphetamine, hadn’t slept for three days, and was becoming increasingly paranoid.

“We didn’t want to exit him from the motel. We wanted to keep him safe,” said Malimban. He met with him several times “to see what I could do, but I was getting nowhere.” Malimban decided to undertake some independent research to learn more about meth and gain a greater understanding of the client’s background.

“We started building a relationship and trust,” Malimban said. Eventually, the client came to him saying he needed help. Malimban organized his rehab treatment and a housing application, which was ultimately successful.

“People wanted a solution. They were ready to do whatever was needed.”

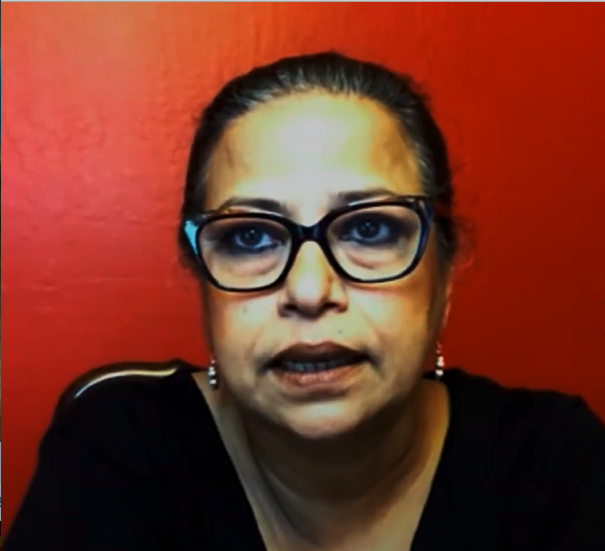

At one of the 200-person emergency shelters not far from the motel, another County employee had bedside talks with clients. Sudha Kalyan, a community and behavioral health worker, provided on-the-spot counseling. She, like Malimban, had also been activated as a disaster service worker.

“Most people had fallen off the map and needed to be hooked back.”

– Sudha Kalyan

Since many clients didn’t have phones, she jumped on hers to coordinate their care, and then connected them to a resource so they could procure a phone.

Some clients who seemed like they might benefit from behavioral health care declined her offer to see a psychiatrist or psychologist, but Kalyan was surprised by how many wanted care. “People wanted help. They wanted to be heard. People wanted a solution. They were ready to do whatever was needed. They were full of gratitude.”

However, many clients didn’t have a primary care physician and were uninsured. Despite often being eligible, they did not have Medi-Cal. “Most people had fallen off the map and needed to be hooked back,” said Kalyan. She, Malimban and other County employees prioritized enrolling or re-enrolling them.

Some people who were unhoused also benefited from being reconnected (in some fashion) to their family, like an elderly man who needed a skilled nursing facility. He had Medi-Cal, but there was a financial issue that needed to be addressed before he could be admitted.

“We didn’t want to exit people back to the streets. We wanted them to be in safer positions in their lives.” – Adrian Malimban

Kalyan hunted down the files of his former case manager and found the client had a son. She phoned him and explained the situation. Although the man didn’t want to reengage with his father, he was happy to cover the shortfall.

95 percent vaccination rate at the Easy 8

When COVID-19 vaccines became available, Malimban, other DSWs at the motel, and health care workers at the VHHP helped 80 percent of the clients at the Easy 8 get vaccinated. That number climbed to 95 percent as time went on.

At first, many clients were skeptical and wanted more information. So, he and his colleagues created workshops and crosswords about the vaccines. They also frequently met with clients to answer questions and coordinate on-site vaccines.

“I called a nurse I knew at the hospital and she brought a mobile van and did a mass vaccination,” said Malimban.

“Foot-on-the-pedal culture”

As the emergency shelter-in-place program stretched on at the hotels and shelters, and the overwhelming majority of clients were successfully protected from COVID-19, the County of Santa Clara started to look to the future. There were widespread concerns that when the program ultimately wound down, it might negatively impact clients who were gaining stability and making headway on their health.

“We didn’t want to exit people back to the streets. We wanted them to be in safer positions in their lives,” said Malimban.

With new interim and permanent housing being built thanks to federal and state pandemic-related funds, rare opportunities opened. For clients to be considered for such housing, as well as added to existing housing lists, Malimban, Kalyan and others urgently completed the paperwork and secured documentation necessary to apply. The speed required to get this done, along with juggling clients’ other needs, matched well with what Malimban called the County’s “foot-on-the-pedal culture.”

“Everyone working across disciplines and departments was like a dream come true in the most unideal of circumstances.”

– Alicia Anderson

“Thousands of people were homeless when we first started at the hotels. And now many of them are off the streets and in permanent housing,” said Malimban. “It’s not perfect, but there are three tiny home communities now, which are all filled, and they weren’t even open at the start of COVID. A lot of it is safety, too. People could have been dead on the streets.”

For clients placed on possibly years-long waiting lists for housing due to the severe lack of supply, some decided to move in with family. Malimban and other DSWs helped reconnect them and organized payment for transportation, often out of state, through the County’s Office of Supportive Housing.

Staff at the hotels and shelters also advocated for critical social services that clients sought, such as food stamps and disability income. They leveraged whatever existing relationships they had and built new ones with employees across a maze of County and city agencies and community-based organizations to secure them.

“Everyone working across disciplines and departments was like a dream come true in the most unideal of circumstances,” said Anderson.

As a result, “clients who had been lost on the streets were finally connected to the County system,” said Malimban. “Before COVID, many were in encampments and had no communication with anyone from the County.” Since then, the majority have received more care and services than before the virus emerged in California.

“We can do these things.” And what lies ahead

Since the pandemic began, the County of Santa Clara has reduced the spread of the virus while increasing medical care, housing, and social services for people experiencing homelessness. “We can do these things” is a key lesson learned during the pandemic, said Dr. Ngo.

“Moving forward, we need to have more resources devoted to the various programs serving the homeless community because sometimes the need is more.”

– Dr. Ngo

Now, as the hotel and shelter program continues to wind down from 14 hotels to three, and clients transition out to housing, family, or back to the streets and parks, many in the County are examining how to build on its success.

“There’s such great momentum during this time. The fear is, we don’t want to lose that momentum,” said Dr. Ngo. “We want to keep that open mindset, continue to communicate, and bridge people and programs while keeping our expectations and quality high.”

He believes burnout is the primary obstacle to building on what he called “this new standard that we set. Staff has been stretched super thin for so long,” he said.

“Moving forward, we need to have more resources devoted to the various programs serving the homeless community because sometimes the need is more,” said Dr. Ngo.

An incredible 5,200 people were permanently housed between January 2020 and September 2021. Now that most of them are hooked up to services, they’ve been seeking care at the Hope Clinic in growing numbers. Dr. Ngo has added more providers and hours to keep up with the increase in demand.

David, to whom we introduced you earlier, is one of Dr. Ngo’s patients. Thanks to the Hope Clinic, he moved out of his hammock and into an apartment where he has easy access to medical care and social services. Today, he describes his once ravaged health as “very good.”

But an increasing number of people need the type of housing and integrated care that David receives.

While measurable progress has been made – and there’s much to be proud of – the problem of homelessness during COVID (and beyond) is far from over. Continued collaboration, creativity, and resources will be critical to harnessing the momentum gained during the pandemic.

This blog is part of a series funded by the California Health Care Foundation